We know we live in an unjust society. Systemic racism, ableism, sexism, ageism, class discrimination, transphobia, discrimination on the basis of religion… it’s all (arguably) more visible than it’s ever been. And – since covid especially – it’s become far clearer how these systemic issues amplify health risks, and more broadly health inequalities.[1]

The Creative Health Quality Framework urges us all to “work towards a more equitable and just society”.[2] And at CHWA, since 2020 we’ve had a roadmap to “building a more equal alliance”.[3] But what does that actually mean? This blog is a chance to tell the story of an ongoing process – one of occasional success, frequent failure, and hopefully some learning.

Let’s start in 2020. A watershed year, in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. That year we recommitted to the idea of an “equal alliance”. We established a basic commitment to five things:

- Committing a % of our budget to build a more equitable alliance

- Gathering and sharing (demographic) information

- Adapting our structure

- Developing our programme and communication

- Reviewing this plan

To be clear, this was a commitment triggered by the Black Lives Matter movement and in response to racial injustice in particular, but these high-level ideas were meant to help us build a more equitable space in relation to all the protected characteristics, as well as socio-economic inequalities.

So, what have we actually done?

The 1%

Every year since 2021 we have committed 1% of our budget – a percentage based on a 2020 recommendation from IncArts. It’s not a huge amount of money, but it means we have been able to pay people to contribute to our now annual Black History Month conversations, for example, or for consultation relating to equity and representation. And when our annual budgets increase, so does this commitment.

Data

We used to do one annual EDI survey and send it to our whole mailing list. This didn’t work; although we have a mailing list in the thousands, the numbers responding were meaninglessly small. So in 2020 we changed two things: first, we started explaining why we’re doing the surveying – so that people know we will actually look at the data; and second, we started to gather information all the time. We hold biennial sector surveys; we ask for information about our Board, staff and the freelancers who work with us every year; we ask for information whenever people join our mailing list, apply for opportunities, attend our national conference, or are part of major programmes. The numbers are still relatively low, but cumulatively we are starting to build up a more reliable and more nuanced picture of who CHWA is engaging with, and where our priorities should lie (see So What? below).

Adapting our structure

CHWA is first and foremost an alliance; the staff and Board are only part of the picture, and we are committed to coproducing in as meaningful a way as possible. In practice what this means is that most of our activities are either designed with the beneficiaries or guided by working groups. We also work with longstanding stakeholder groups – national and regional – to make sure our work remains attached to the reality of practice.

We build working groups to be as representative as possible. And in bringing together the working group for the quality framework, for example, we started to formalise this process, considering four factors: 1. Representation of protected characteristics; 2. Representation from different regions of the country; 3. Representation of different types of practice, organisation, or experience, and 4. Representation of people who have lived experience of ‘creative health’ as a participant. We then asked the group who was missing – and filled these gaps. This is by its very definition a tick-box exercise, but if we don’t do it, we end up with the same ‘experts’ in every group.

We now have to make sure we don’t just replicate groups and create a reliance on the ‘usual suspects’: many of our colleagues of colour tell us they are called on time and time again to appear on panels and in groups (often unpaid). This means starting from scratch every time and making new contacts – time-consuming and sometimes awkward work, because it can depend on approaching people outside your networks who frankly have no reason to trust your intentions.

We’re also working to make our longstanding stakeholder groups more diverse. This has proved much harder. We tried changing the way we recruit champions, for example: we spent time and money approaching diverse-led local organisations to engage with new people in advance of recruiting. To an extent this worked, but since we only recruit when someone steps down (occasionally), we were bringing in maybe one or two people from marginalised groups, which then untold pressure on them to “represent” their demographic. This was wildly counterproductive, because we didn’t have the in-house capacity to provide the right support. It’s a version of the story we hear a lot – where people early in their careers are brought into organisations as ‘changemakers’, without the organisation changing its structure to support them; so in the end, unsupported, they leave. It’s as harmful as putting a new plant in the wrong soil.

So we’re trying to think about the soil; and we’re working on the basis that if we’re not attracting a diverse contingent of people, we need to change the role. This is very much a work in progress, but thus far we’re removing any obligation – tacit or overt – to “represent” anything – whether this is a geography or a type of practice or a demographic; and instead we’re offering more to champions (leadership development for example) and asking less; no more unpaid work to build infrastructure.

Developing our programme and comms

We are all the time trying to shift the emphasis from pure ‘health’ to health equity. In practice this means, for example, bringing health inequalities and justice into any training programmes; and ensuring that public definitions of creative health include equity. The clearest example here is the Creative Health Quality Framework: Equitable is one of the eight principles that govern the work (and it’s there precisely because of the way we built the working group).

It's also about more obvious things like the content of our bulletin and site: ensuring visible diversity; engaging with key dates like Black History Month and Disability History Month; making sure we include information on racial justice, anti-ableist work, and climate justice in each edition. Often we’ve delayed bulletins to try to improve the content. Often, to be clear, we haven’t got it right; the biggest spur to improving our bulletin came from a colleague pointing out our failure to focus on Black History Month – and I remember that email every time I think we won’t have time to do anything as substantial as we’d like to.

Reviewing this plan each year, listening and learning

Over the last 18 months in particular we’ve been looking at all of this and coming step by slow step to a new action plan, of which more below.

So what?

Has any of this had any impact? Well, yes and no.

Now that we have more data, we can make a few generalisations about the demographics of the people engaging with CHWA (in comparison to census data on the general population): We are very diverse in terms of both sexuality and neurodiversity. A large proportion of us have caring responsibilities. The number of people identifying as Disabled is roughly representative of the national population. Women are vastly over-represented (80-90%). In terms of heritage, people of African and Caribbean Heritage, Asian heritage and Gypsy/Roma/Traveller heritage are all under-represented. People of mixed heritage are approximately represented. The socio-economic data is much harder to analyse confidently; a project we need to tackle this year.

If we want to be representative there is clearly work to do in some quite specific areas. But – perhaps more importantly – if we want to speak to systems change, and supporting leadership from the margins, we need be more than representative – we need to create an alliance which cultivates a sense of belonging, in particular for people who have been systematically marginalised by our current systems; without that, the impetus for systems change will simply not be strong enough.

Although our conference last year was by any measure the most diverse event we have managed, global majority colleagues still told us they felt a unsafe and uncomfortable, because it was just not diverse enough. Ultimately if people don’t feel they belong, all we’re doing is replicating the systems we’re trying to dismantle.

Where we have seen change is in the makeup of our Board and staff: 20% identify as Disabled, and we’ve seen a significant shift away from more affluent socioeconomic backgrounds (from 56% to 30%); and a reduction from almost 80% identifying as white to 60%. Much of this has been down to changing our recruitment processes, in line with thorough guidance from IncArts Unlock, Curating for Change, and Creative Access. (If you’re interested, a full check-list is included as an Appendix in our Equality Action Plan.)

This has made us start to think differently about three different groups: Where we can have a fairly direct impact (Board, staff, stakeholder groups). Where we can influence (members). And where we need to listen and amplify others’ work across the wider sectors we work with.

At the same time, new areas of focus have emerged:

1. Fair Pay

We know that much of the structural inequity in creative health is connected to the precarity of the work; and to the persistent devaluation of practitioners’ skills and experience. This makes it far harder for people without independent means to build sustainable careers in creative health.[4] CHWA has formally been a Real Living Wage employer since 2022. And after a year or so of trialling this approach, in 2024 we introduced a policy on payments for freelance and low/un-waged colleagues – to ensure people are paid whenever they contribute their expertise to help develop CHWA's work. We’ve now extended this to our Board members, so that they too are entitled to partial payment for supporting CHWA.

2. Access

We’ve recently published a guide to accessible events in creative health based on what we learned from our 2023 conference. We introduced video and audio options into all our recruitment, commissions and awards processes in 2021. This year we began producing video versions of every monthly bulletin. Our online events are built with neurodiverse audiences in mind. But there is a lot more we need to do to understand how we might better connect with and open up our resources and support to colleagues identifying as Deaf and disabled.

3. Wellbeing

The wellbeing of the people delivering this work has perhaps been our members’ most consistently voiced concern since we began working in 2018. Risks to wellbeing are amplified for people identifying with protected characteristics; again, we can’t talk about wellbeing unless we talk about equity. It's also clear that you can’t deliver wellbeing to others if your own wellbeing is not supported – ignoring this sets up a dangerous assumption that you are not as vulnerable as the people you work with. There are so many organisations that articulate this interrelationship brilliantly – Kazzum and Healing Justice London are just two of them – and recent moves towards “trauma-informed” practice feel like a very positive shift, and a helpful way to understand intersecting risks at a personal, community and political level. Internally, we try to take this very seriously in terms of our working practice – much of what we do is about reducing outputs, and slowing down. It’s not always successful – it’s very hard to slow down when everything about the culture is predicated on an anxious rush to produce (and consume) – but from my own experience, the faster we produce, the less inclusive we are, the less we examine discomfort (our own and others’) and the more inclined we are to ride over it as if it doesn’t matter.

This wellbeing problem is nowhere near being solved, but there’s no question that funders in particular are recognising the need to support practitioners’ wellbeing in ways they did not six years ago – thanks to a concerted effort from numerous organisations. A new resource on practitioner wellbeing is coming soon, based on research commissioned by Arts Council England, by Julia Fortier and Kate Massey-Chase – and the University of Wolverhampton is also taking leadership in this area. The recent Clore Leadership work is also a welcome step in taking this issue seriously for leaders in the cultural sector.

4. Solidarity

As a national organisation that seeks to give both guidance and support to a broad range of people, we often respond to external (political) circumstances. We comment on government policy, for example, as it relates to creative health.[5] But more than this, we sometimes need to refer to public events beyond our immediate mission, but which clearly conflict with our principles – and particularly events or political decisions that have a disproportionately adverse impact on the health or wellbeing of colleagues identifying with protected characteristics. This is a tricky area. We don’t have a tight organisational policy (yet) on when we should make public statements – and we’re very conscious of the risk of tokenistic virtue-signalling; we tend to work this out with partners, the team and Board on a case-by-case basis, but solidarity with other organisations and campaigns that seek to redefine health and wellbeing is moving to the heart of our new action plan, and we need to do our best to live up to this commitment.

What now?

Something started troubling us about the “roadmap” to a more equal alliance. It seemed somehow tacked-on, and woefully absent from our governing theory of change. Those of you who run small organisations will know how theories do tend come after practice; you build a scaffold after you’ve already got half the tower up, when you start to realise there are too many wings and it might all just topple over without some governing logic. This is how our theory of change came about; but it wasn’t quite the right logic. To extend the metaphor, it was somehow not supporting the core of the building. So we’ve started from the ground up. I’m not sure we’ve got it right yet but equity is much more central to the structure than it was.[6]

And this allows us to make a more realistic action plan, too.

A critical step has been understanding the difference between what we can impact, where we can influence, and where we should just shut up and listen. Although justice has to be at the centre of CHWA, CHWA is by no means at the centre of justice. We are what we are – our history is messy and whilst some of our roots are in social justice and radical reconceptions of health and creativity, some are in more complicated spaces of privilege of various kinds – my own start in public hospitals 25 years ago was absolutely rooted in the elite worlds of galleries, and paternalistic ideas about the arts’ healing (educational) powers. It was a time when Mozart was considered the only music that was “good for you”, when “abstract art” was considered actively dangerous for hospital patients. We’ve come a long way (I hope) but there’s no point denying that this is part of the creative health journey, and it will have alienated plenty of people along the way. We have to try actively to counterbalance this. This may be part of the “anti-” bit of anti-racism and anti-ableism – unlocking the traps in our history.

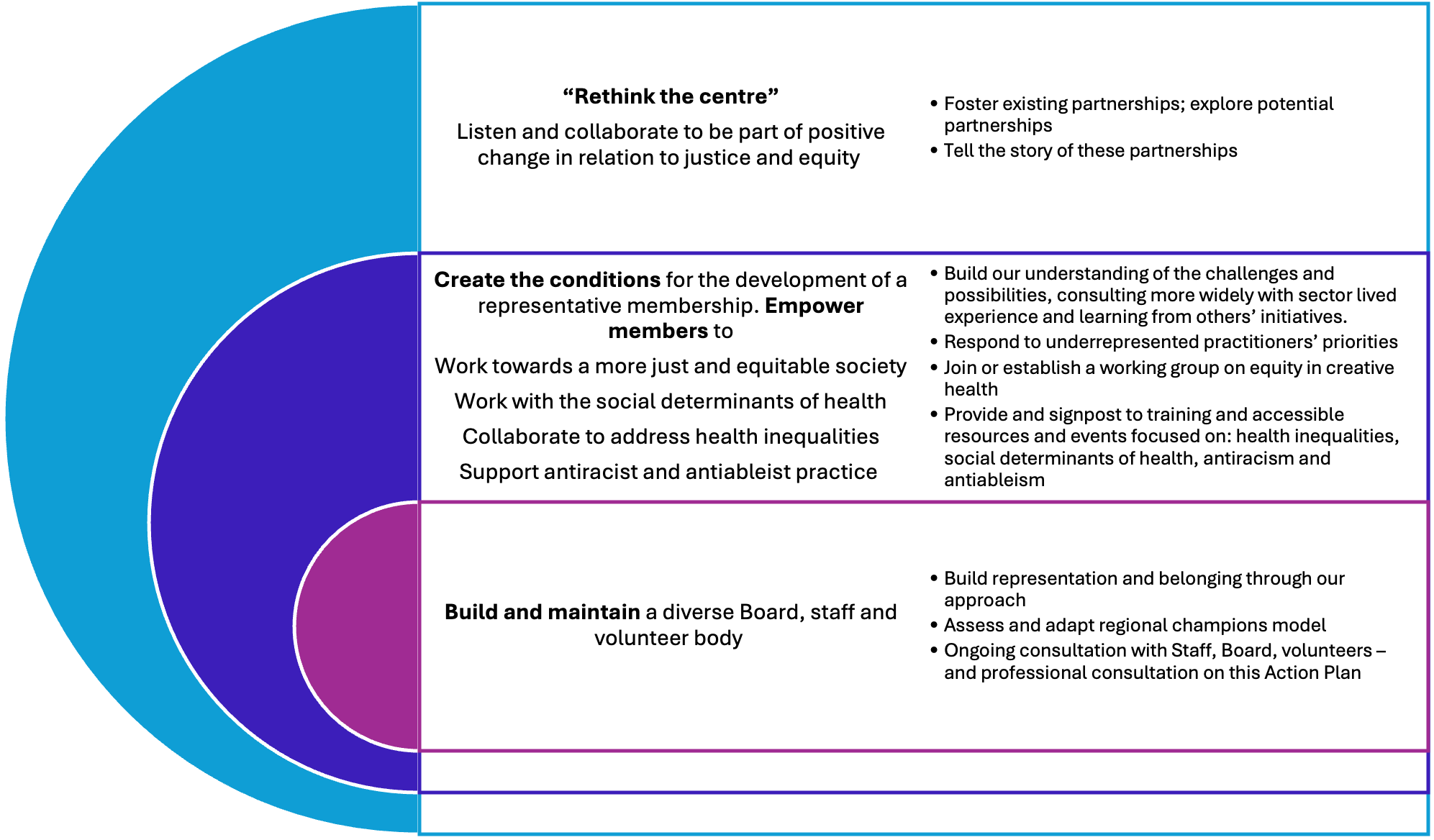

So this is where we have come to:

Of course this doesn’t look all that meaningful, so here’s one concrete example for each circle: in that largest circle, we have partnered with ASON (the Arts & Social Outcomes Network) to produce a Fair Pay and Lived Experience Manifesto and Resource, and we’re going to convene a meeting of funders to address the question of coproduction and how to properly support this process taking into account the time and effort it takes to really coproduce. In the middle circle, we’ve been training our regional champions and Working Together partners in understanding health inequalities and how to be part of the systems that might tackle this. In the smallest circle, we’ve introduced wellbeing budgets for staff and better internal communications systems.

Before we formally launch the full plan, we want to consult with an equalities expert, but look out for a version of this later this year. Another slow step on a long journey.

References

[1] Prof Kevin Fenton summarises this brilliantly in Laura Bailey’s Creative Health podcast: https://creative-health.co.uk/podcasts/professor-kevin-fenton/

[2] https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/resources/creative-health-quality-framework

[3] https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/roadmap-building-more-equal-alliance

[4] See From Surviving to Thriving, CHWA/Baring Foundation, 2023 (pp.22-5).

[5] For example: https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/news/blog/new-government-interested-creative-health

[6] https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/theory-change