Last month, Arts Professional published an article of mine. It made the case for a substantial new income stream for the arts sector which could go hand in hand with significant savings to the health budget. To make progress, we must leave some old assumptions behind.[1]

This blog is about one of these assumptions: that arts-and-health work is a compromise. The more you engage with health issues, practices and systems, the less artistic scope there is. From Aesop’s experience this is a false tension. At its best, artists and health and social care workers collaborating on arts-and-health programmes set up virtuous circles between high-quality artistic practice and health improvement.

The arts-and-health ‘compromise’ is one symptom of a curse that is at least 20 years old. Back in 1999, the Government’s Department for Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) set up Policy Action Team 10 to report on ‘using arts, sport and leisure to engage people in poor neighbourhoods, particularly those who may feel most excluded, such as disaffected young people and people from ethnic minorities.’[2] For some in the arts this was an exciting new opportunity to demonstrate the power of the arts to transform lives. For others, it forced the arts to be an instrument of Government, devalued the intrinsic value of the arts and stifled artistic freedom. The battle of ideas continues today.

The lobby for the arts’ intrinsic value gained ground in 2008. The Government published a report from arts leader, Sir Brian McMaster, called ‘Supporting Excellence in the Arts – From Measurement to Judgement’.[3] The DCMS Secretary of State’s foreword included this: ‘It is also time to trust our artists and our organisations to do what they do best – to create the most excellent work they can – and to strive for what is new and exciting, rather than what is safe and comfortable. To do this we must free artists and cultural organisations from outdated structures and burdensome targets, which can act as millstones around the neck of creativity.’

Fast forward to the Arts & Humanities Research Council’s Cultural Value Project report of 2016, ‘Understanding the value of arts and culture’[4]. Neither side had prevailed. ‘Our key aim [of the Cultural Value Project] was to cut through the current logjam with its repeated polarisation of the issues: the intrinsic v the instrumental, …’.[5]

The battle of ideas limps on but what are we practitioners to do? Aesop’s experience has been heartening. Our vision is ‘A future when arts solutions for society’s problems are valued and available for all who need them’. Key to breaking the ‘logjam’ is Dance to Health, created to be an arts solution to older people’s falls. Inspiration came from important Age UK research into older people’s falls and the UK’s brilliant community dance sector. Along the way we have learnt three crucial lessons.

The first is that arts solutions to health challenges are created by artists and health professionals working on a problem together. We organised a lab in early 2015, bringing together dance artists and falls prevention exercise experts. They talked, went into the studio to exchange practice and try ideas out, and emerged with a shared hunch that dance could add something to falls prevention. Here were two professions building a bridge based on mutual respect.

The second came from the Pilot Programme in 2016 and 2017. We paid for a group of dance artists to qualify in falls prevention exercise and then translate exercise programmes recognised by the health system into community dance. Could this done in a way which was creatively rewarding for the dance artists and enabled them to develop their creative practice? If the answer was ‘no’ then dance artists would not have enough artistic scope, recruiting more dance artists would be impossible and Dance to Health would have no future. To our great relief the answer was ‘yes’. Translation of the exercise programmes was an enjoyable challenge for dance artists:

- ‘I push other older people’s groups much harder now than before.’

- ‘I now have a more confident approach to articulating the health benefits of what I do and being able to speak about what I do from a more informed perspective.’

- ‘It pushed my own facilitation practice. I felt enriched. Every time I went in, I learned a lot.’

- ‘I learned from the specificity of why you do a movement and the benefits – I will carry this over into other work.’

Here was strong evidence that more you engage with health issues, practices and systems, the greater artistic scope.

We learnt the final lesson from the much larger, £2.1 million ‘Phase 1 Roll-out [Test & Learn]’ programme of 2017 to 2019. We now have evidence that artists and health and social care workers collaborating on arts-and-health programmes can set up virtuous circles between high-quality artistic practice and health improvement. It is one of many lessons identified in the overall evaluation[6].

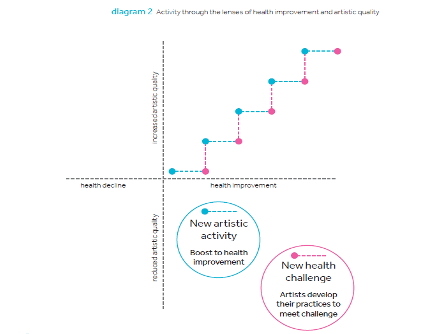

The idea is best presented through this diagram in the evaluation report.

The diagram separates out the artistic and health dimensions. It acknowledges that not all arts activity improves health and that the degree of health improvement or decline will vary according to the quality of the artistic activity. For example, singers in choirs know the difference between a great choral director and an unsatisfactory one: the ability to inspire regular attendance, choose interesting repertoire and lead an excellent performance. Working with a poor choral director may lead to frustration or worse. Health outcomes will be affected by the quality of the choral director.

The top right hand quadrant is where the good work is done.

Horizontal blue-line progress happens when the arts sector responds effectively to a health challenge. Sheffield Hallam University evaluated Phase 1 and concluded that ‘Dance to Health offers the health system an effective and cost-effective means to address the issue of older people’s falls.’

Vertical pink-line progress happens when a new challenge is added and artists respond successfully. For example, Phase 1 included four Royal British Legion care homes. In one we were asked to deliver the programme in a dementia unit. Dance artists used their artistic creativity and expertise to develop Dance to Health in ways which engaged participants with different degrees of dementia and different physical abilities. They also enthused the care staff. Every session involved everyone in the unit.

We must move on from this cursed logjam. With the health, social and economic tragedy of Covid-19, we must move on fast and on a much larger scale. We have many brilliant artists in this country ready and able to make a vital contribution. Echoing Arts Council England’s 2020-30 strategy, ‘Let’s create’ artistic solutions for all who need them.

[1] https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/magazine/article/arts-and-health-think-big-and-embrace-opportunities?utm_source=subscriber_features&utm_medium=email&utm_content=nid-214480&utm_campaign=23rd-July-2020

[2] https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.culture.gov.uk/reference_library/publications/4728.aspx

[3] http://data.parliament.uk/DepositedPapers/Files/DEP2008-0790/DEP2008-0790.pdf

[4] https://ahrc.ukri.org/documents/publications/cultural-value-project-final-report/

[5] https://ahrc.ukri.org/documents/publications/cultural-value-project-final-report/ (p.6)

[6] https://ae-sop.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2020/06/AESOP-Dance-to-Health-Phase-1-Overall-evaluation-Report-April-2020-FINAL.pdf