I write this short reflective piece as I retire from my role as manager of Healing Arts for the Isle of Wight NHS Trust at the end of August 2019, having arrived to work with the then Isle of Wight Health Authority in June 1986.

Anyone who has been with the NHS knows there has been many subsequent reorganisations of the structure and doubtless there will be more to come, however my role has been constant in that it has been as part of the delivery arm of the NHS in acute and community healthcare, primary and secondary provision of services – rather than the present commissioning arm. The two used to be co-consistent and life was so much easier then!

When I arrived my brief was twofold.

First: to create a healing environment in the newly designed and being constructed District General Hospital at St. Mary’s, Newport. I was asked to develop and commission artworks and activity for as many areas of the hospital as possible. Particularly the wards and areas in which people were receiving treatment as inpatients – experiencing and hopefully recovering from illness – and in those areas for outpatients where people were being monitored, supervised, advised, tested, learning to manage their health condition, etc.

However, the environment also includes other important spaces, such as the large amount of public space and corridors, work environment for staff, restaurant, chapel/mortuary and outdoor spaces. This role has principally been accomplished through acquiring a collection of paintings, sculpture, mosaic, textiles, ceramics, glass works, photographs and lightboxes and items of heritage. However, interior colour decoration schemes, furniture and architectural features are equally important, most recently with the 'Patient-focused Gardens'. The Isle of Wight NHS Trust now has a collection of 2,000+ artworks on permanent public display.

Second: to develop a programme of arts activity – music, creative writing, dance and movement, singing etc. for people with ‘health conditions’ across the spectrum – from respiratory conditions to mental health, ante- and post-natal care, bereavement, neurological conditions, allergies, weight/diet/exercise etc. – to participate in either individually or in groups. These have principally been delivered as part of community healthcare and for daily living and home environments to enable people to manage and understand their response to their condition more successfully, to prevent occurrence and re-occurrence, and to promote healthy living and wellbeing.

In response to the endless calls from commissioners to “give us the evidence and prove the cost-effectiveness and cost-benefits” of arts and health activity, we developed a series of research projects – ‘Moving On’,‘SoundStart’, ‘MusicStart’, and ‘Time Being’, whose results are published on the Isle of Wight NHS Trust website here: www.iow.nhs.uk/healingarts. Reports and other archive documents are housed at the Wellcome Library, Euston Road, London.

Reflecting on what arts and health programmes essentially achieve, after the Arts Council England/Department of Health Prospectus (2007) and the All-Party Parliamentary Group's Creative Health report (2017), my view remains the same as when I arrived new to the scene in 1986. Trying to make sense of it then I was much impressed by Dr Linda Moss’ short paper where she defined and described health as having 3 principle constituent parts. Curing – Caring – Healing. The first is the medicine and science and principally the role of Doctors. The second that of Nurses and Health Professionals. The third – Healing, is the individual themself who is central to the effectivness or otherwise of the situation. Whilst there are contributions that Artists can make to both curing and caring, I decided and still think so the principle way of the arts most effectively contributing to ‘Health’ is a through the healing process. Others contribute to this as well – Chaplaincy and spiritual guides, relatives and friends, mentors etc. As a consequence I think the role of artists in healthcare is best seen as part of the study of Anthropology, the discipline where knowledge, practice, experience and studies meet linking the humanities with the sciences. The Wellcome Arts and Health Collection seems to me to support this concept, as do the collections in our Galleries and Museums of Arts, Humanities, Sciences and Technology.

Reflecting on what activity has worked best, I think the paramount and critical and crucial issue is the recognition of the professional status of the artist for their contribution within healthcare alongside other healthcare professionals – both via healing, caring, curing, and in terms of financial and contractual status and recompense. Unfortunately I think the NHS – Trusts and GPs – still have some way to go in recognising this and the CCGs and Commissioners still a very long way to go. This issue the arts and health community – particularly the Culture Health and Wellbeing Alliance – must give its full attention to.

In our ‘Time Being Stroke’ research programme we developed the concept of a team of artists – multi-artform, working as part of the clinical multi-disciplinary team (MDT) on an acute hospital Stroke Unit with Consultants, Doctors, Nurses, Physio, Speech and Occupational Therapists in the treatment, recovery and discharge of individual patients. Each professional group acknowledged and understood their respective role in a person’s programme of treatment and care, with the arts being prescribed on an established set of criteria. This seems to me the proper and most effective way of delivering the arts as part of the healthcare services in an acute hospital. Initial costs in setting up the team are required, however once up and running, and through a peripatetic form of delivery across departments, this can soon establish the cost-effectiveness and cost-benefits that arise and make the case for the arts as an integral on-going part of healthcare.

In effect this is no different to the function and structure of the allied health professional teams of therapists etc. The principle obstacle seems to be the lack of vision and understanding of the contribution the arts makes to health in the senior healthcare managers of the NHS and commissioners. This is in part due to our nation’s culture, where the arts are separated from the sciences and humanities at around age 11, and the consequent belief that the arts are largely peripheral, with science as the most important force and influence of progress in society. There is a deep latent fear, lack of confidence and temerity about engaging with this field of activity – the arts – as adults. Artists as professionals might be untrustworthy, unpredictable, unreliable, individualistic and not team players. A lot to sort through! This seems to me to be the unspoken but probable view of most health managers and commissioners.

However, making artists part of Hospital MDTs seems to me the best long-term approach and objective. This also applies to the environment, with artists working as part of the Architectural and Estates/Capital teams responsible for designing new and upgrading and maintaining existing buildings. This worked well during the Arts Council's percent-for-art scheme and they should be encouraged to seek to reinforce this again with the Department of Health.

The other form of delivery that has worked well is the Artist-in-Residence. We developed this in single art forms – primarily Music and Singing, and Creative Writing. The artist was given the brief to define and develop the contribution their artform and practice could make across healthcare departments and health conditions. So in the case of the Musician-in-Residence, this developed with programmes for ante- and post-natal healthcare with people prior to birth (6 months) and following (up to 5 years), as well as their parents. The musician and team also developed programmes in mental health, learning disabilities, respiratory conditions and living with long-term health conditions (neurological, cancer etc.). The ‘Writer-in-Residence’ also developed practice, particularly in mental health and primary care and with GP referrals and established links with the wider healthcare community in prisons. The advantage of this type of role, once established and regularly funded, is that it can be passed onto to successive occupants/appointments and the programme continuously re-defined and readjusted to respond to demand and change, enabling the arts-and-health manager to build a peripatetic team within their NHS area of influence and benefit. My regret is that it has never been possible to date to obtain the funding for this on a continuous basis via the NHS after the Provider/Commissioner split/reorganisation of the NHS in the mid 2000s, with funding seen from then on by the NHS as the responsibility of the Arts Council or the Charitable Trusts and Foundations sector. Essentially they will only fund on a project basis, meaning that you constantly have to reinvent the wheel, and there is no continuity of healthcare service as a person can and would expect from consultations with their doctor, pharmacists etc. If arts and health is to receive professional recognition, this continuity of service and availability to the individual is essential certainly for the duration of a health incident and most especially for long-term and lifelong health conditions.

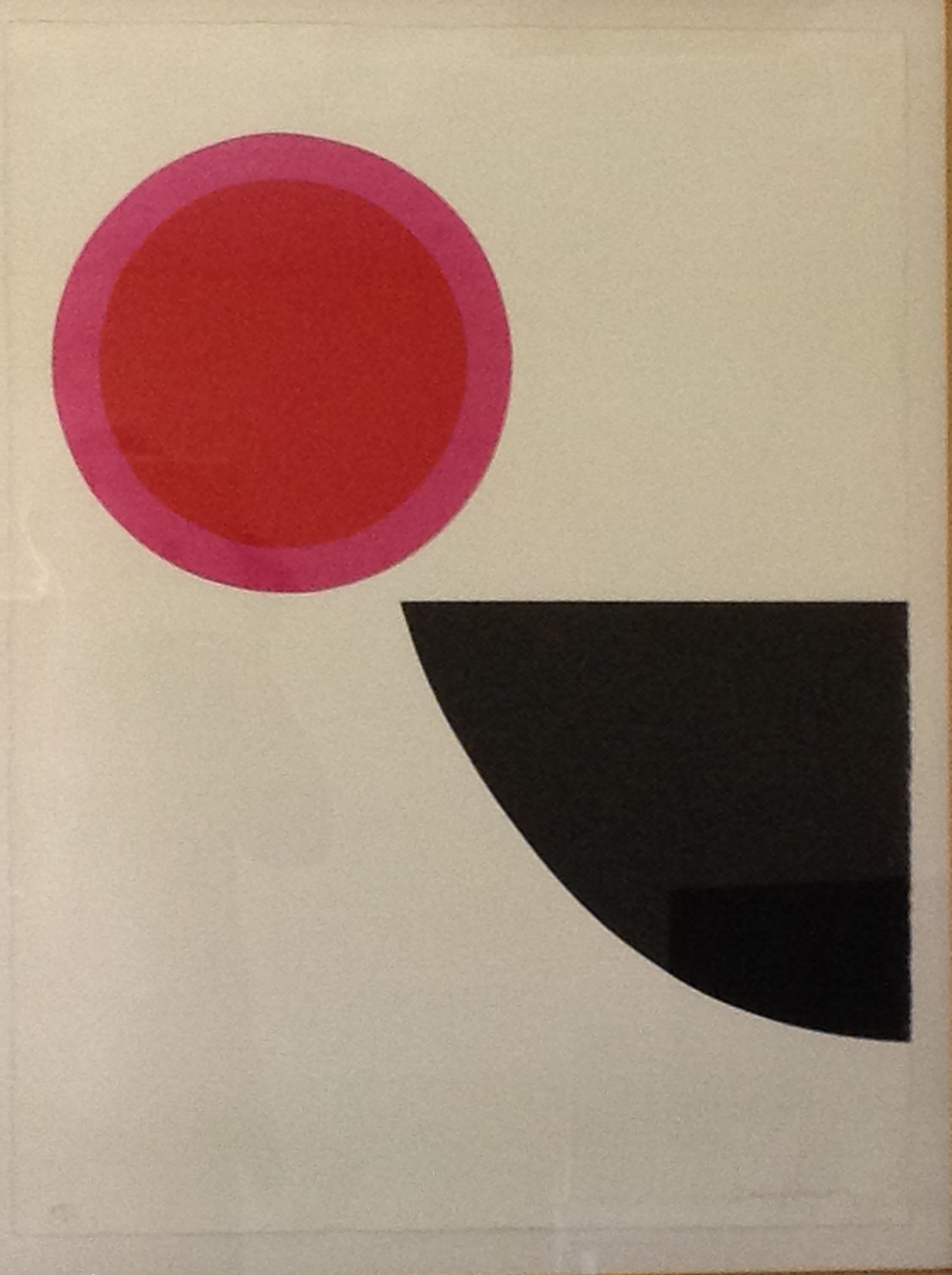

In conclusion: A comment on the importance of remaining impartial when deciding and discussing what art works and what doesn’t. Attached are 2 images . The abstract image of the black quadrant and red/pink circle is by Royal Academician Terry Frost. The image of the cows and a girl crossing a bridge was donated a long time ago – pre-1986 by a local ‘amateur artist’ P. Hibbert so I know little about its background. A person visiting my office on seeing the Terry Frost commented “I can’t see the point of this sort of art – what does it all mean?” Very difficult to give a convincing response unless there is some prior empathy or experience. Another person on seeing the P. Hibbert said “Why on earth have we got this in the collection – where does it come from?” Very difficult to convince them of its artistic skill and value. However the P. Hibbert picture was displayed for a long time in the office of a Psychiatric Nurse who told me that a patient of theirs had found it incredibly meaningful and it reflected an incident in their childhood and they attributed to it significantly enabling them to achieve their recovery. Quite a commendation. Whilst the Terry Frost I love. It has been in my office over the years. However, although few people like it, it reflects perfectly the way I have felt all this time delivering this role as the manager of Healing Arts – as the circle suspended in the air, hovering in space, precariously balanced against colliding with the sharp black point of the quadrant and spinning off in an uncontrollable direction. Both work. Beware of making judgements. People's testimony must be paramount.

You can contact Guy at [email protected]